So yesterday I embarked on this mad, audacious goal of trying to create a front-end framework from the ground-up using TDD and TypeScript. For those of you who’d like to refresh your memory, you can find the original blog post here. But what does the world look like today? Well. There was midnight oil burned and coffee drunk. There was trashy background TV watched and lots of lovely downtime. My Trello board now looks liiiiike this!

Now. You may notice in this screeny that I am my own User. I am Dev, QA, BA and PO. I am literally wearing every single hat. And this is really tough. I am answerable to nobody. No acceptance criteria are challenged. The overall design of The System is arrived at with no input from other developers. I am drawing on the experience of a single person, and the testing of The System is not validated by anyone other than the person who originally developed it.

And it’s kinda freeing, in a way - but also pretty lonely. Pet projects such as these really bring home how privileged I am to work with incredible people every day, and how much fun I get to have working in tech! But enough of that fluffiness, what have I actually achieved??

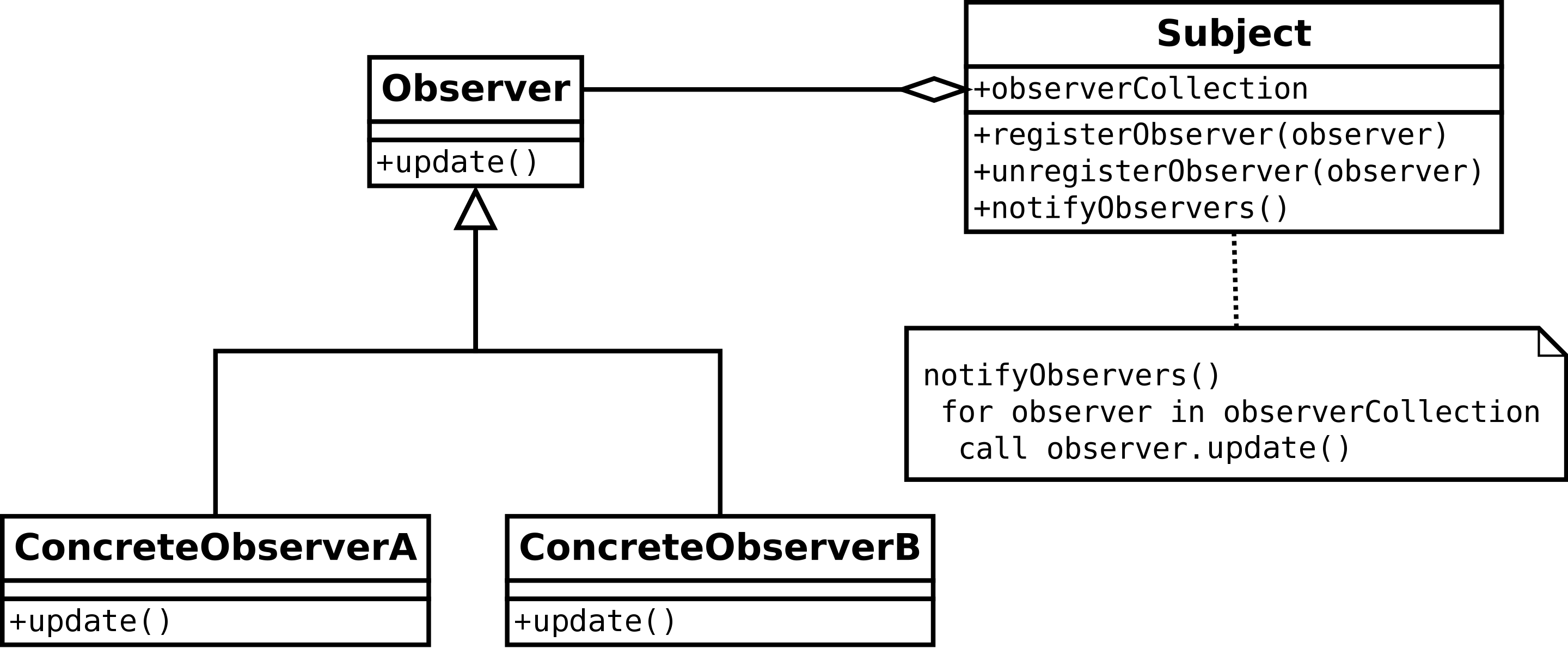

The Observer Pattern

So this is ancient, right? If you’ve not come across it there’s a super book you should take a look at! Simply put this pattern allows changes in the state of one component to Notify any number of Observers. The way it does this is actually pretty low-tech. You essentially have a RegisterObserver method on your Observed component which adds new Observers to an array, and then you iterate over each of these Observers and notify them whenever your state changes.

Now, I’ve decided to use this pattern as a means to keep my DOM updated with any changes that might happen in the structure of whatever State-object-thing I’ve got defined. Let’s see if we can drive out that behaviour using tests!

Test #1 - Observers are registered

In this test I’ve created a couple of in-test components to start investigating

observability. There’s a dead simple registerObserver function that belongs to my

Controller class. Right now it should be adding the provided observer to a collection

so that we can subsequently used it to notify the world when something changes. But right now that’s not happening. Let’s fix that :fist:

It’s really that simple… Arguably this first test might be doing too much, but coming in at only 20 lines of code (including assertions); I’m pretty happy! Shall we refactor? I think we should. Right now we’ve got all the code in a single file. This is gonna get pretty hard to organise and maintain as the app grows, so let’s move things about a little bit?

Splendid. Now we have a few separate .ts files which represent the functionality of a

couple of very well-defined components. I’m pretty happy with this folder structure for

now so let’s move on, I guess? BUT WAIT! There’s a problem with the design. Right now

we’re exposing the Controller’s Array<Observable> member as a public property. This

is kinda dangerous as it’s no longer under the direct control of the Controller class.

Any class that has a reference to our Controller can update, reassign or delete the

Array’s contents. Side effects are naughty! Let’s make it private, but still provide

a mechanism to list its contents.

This is almost a trivial refactor again, but now the collection is defined as being private

and readonly. We also now have a get function which returns a mapped collection of the

original list of observers. Fab.

Test #2 - Observers are notified

So now that we’ve found a way for Observers to be registered with our Controller, what about being able to tell Observers about changes to state? Let’s write a test to drive this out. We’ll start by adding a simple prop, then writing a test which asserts whether or not any registered Observers are notified when it changes. The below gist is what I ended up with!

Here I’m using a simple TypeScript getter/setter combo to hook into the setting of a simple property, and using that as a springboard to iterate over all the Observers and update them with the value that’s changed. It doesn’t feel like this is a particularly scalable approach, unfortunately :cry: - what happens when the number of props change? I really don’t like the idea of every single Controller implementation to have to know about how to notify observers, and it feels a bit smelly to have to repeat this for every single property in my state.

Enter Proxy

The Proxy design pattern is a popular one within the JavaScript community. It’s essentially

a mechanism to trap properties with handlers which you can then decorate with additional

functionality. Though the Proxy class gives you loads of different types of functionality

you can configure, I purely want to use the set trap for every property of my

Controller’s state. Let’s see what I ended up with (after a bit of soul-searching!!)

There’ve been a few iterations to arrive at this design, but the crux of it is that:

-

The

Controllerclass is now abstract. To use its functionality, you derive your own implementation of Controller. The management of Observability is handled by the superclass so we no longer have to worry about it! -

Derived

Controllerinstances now need to provide an implementation of a function calleddata. This function returns a plain-old-javascript object which defines the initial state of theController. Each Controller derivative is going to use this state variable for the day-to-day gubbins of Controller management/lifecycle etc. -

The

constructorof theControllerclass initialises a new, protected property calledstate. This Proxy variable provides an implementation of thesettrap which simply iterates its Observables and callsupdate.

That’s kind of it! There are tests and such, also - you can find all the code at my Github..

Next time we’re going to continue to expand on this idea of observability by tying in a dependency on the real-life DOM!

Peace :sunglasses: